The SS STRAITHAIRD had come from Southampton via Cuxhaven to go to Port Melbourne, Australia. The voyage took five weeks. The service on board the P & O Liner was excellent. At mealtimes we had a table-steward to look after eight people at our table.

Our steward was Irish and always quick on the move. He assumed, everyone would be eating all three courses for every meal. That meant, he usually had the dessert already waiting on his serving table before everyone had finished their second course.

One day two people refused to have dessert. Our steward looked pleadingly at me and Peter, for he knew us to be good eaters: We always emptied our plates!

“Please, would you like a second dessert? See, I am not supposed to take it back to the kitchen,” he said. My husband and I gladly accepted a second dessert. It was delicious! Since our steward could not help being a bit rash with the ordering, quite a few more second desserts came our way during the following weeks. We did not mind this at all. Actually we were rather glad to help out!

Month: March 2012

Memories from 1974

The other day I came across some notes I made about some conversations in our

family towards the end of summer of 1974 when Gaby was sixteen, Monika fifteen, Martin close to fourteen, Peter close to thirty-nine and I also thirty-nine.

ONE AFTERNOON IN FEBRUARY 1974

Gaby, my daughter, sits close to the open door in her wheelchair. Peter, her father, helps her to sort out her record-club order.

I take notes of the following conversation. I am outside close to the open door and I am stretched out on the lawn under a large umbrella.

Gaby: I should’ve written on that form ‘please hurry’. Gee, I’m glad I’m going to get that record at last. Will you put all this away now, please?

Peter: Wie, das willste auch aufheben? Das ist doch nur Reklame, Menschenskind!

What, you’re going to keep that too? These are only adds, for heaven’s sake!

Gaby: I keep everything from the record-club.

Peter: So, wo kommt das hin? So, where does this go?

Gaby: Right at the back of the folder. It’s nice paper, isn’t it?

Peter: Nee.

Gaby: That’s the second record I’ve ordered. Are they going to send me a receipt?

Peter: No, das ist covered. The balance is going to show it. Kommt das hier rin?

Gaby: No, it goes into the blue folder.

Son Martin comes up the ramp. He carries his school-case., greets me with ‘Hi, Mum’, enters the house. A little later daughter Monika follows, also with school- case and saying ‘Hi, Mum!’ I say ‘Hi, Martin! Hi, Monika!’ As Martin enters the

house, Peter and Gaby are still deep in conversation.

Peter: Martin, was sagt man denn, wenn man hier hereinkommt? — Good-day!

What do you say when you come in here? — Good-day!

Martin: You were talking.

Monika says ‘Hi’ as she enters. And Peter says: ‘Hallo, Monika!’

A bit later Peter and Martin talk with Gaby about her school-certificate.

Martin: That bit of scrap-paper, is that all you’ve got?

Peter: Mehr braucht se doch nicht. Das ist das certificate.

She doesn’t need anything else. This is the certificate.

Martin: Actually you shouldn’t have passed since you didn’t work right through

the year.

Peter: Hat se gut gearbeitet, hat se auch bestanden.

Oh, she worked well, that’s how she passed.

Martin: But she didn’t arbeite gut. She didn’t work well.

Peter: Nun lass man gut sein. Sie hat schon gut gearbeitet.

Now leave her alone. She did work quite well.

A bit later

Monika: Gee, it’s hot! Pat and Donna are coming in a minute. They want a lift over to

Warilla Grove. Who’s going to take us to Warilla Grove? It’s late already, you

know?

(calling from outside)

Uta: Papa’s going to take you!

Monika: Better hurry up!

Gaby: Papa, don’t forget to mail my record-order! The letter-box gets emptied soon!

Peter: Wann musst Du auf der Arbeit sein, Monika?

When do you have to be at work, Monika?

Monika: We have to leave within the next five or ten minutes.

Peter: Ich fahre erst tanken. I go to get some petrol first.

Peter leaves in a hurry.

Pat and Donna come up the ramp. Monika greets them and goes inside with them.

I hear a terrible noise from the neighbours’ backyard: One of their sons goes on his mini-bike round and round in the backyard.

A bit later Wayne comes up the ramp. He carries a beach-towel.

Uta: Hi, Wayne! Do you want to go to the pool with Martin?

Waine: Yeah.

Uta: Best thing you can do in this weather!

Waine: Yeah.

Wayne enters the house. Peter returns from getting petrol. Soon after he leaves with Monika, Pat and Donna in the car. (At Warilla Grove Monika is going to get some training at the Woolworths cash register.)

Martin and Wayne leave for the pool. The mini-bike has stopped making

noise. I enter the house.

Gaby: Heh, Mama, you have to buy some food today, don’t you?

Uta: That’s right.

Gaby: When are you going?

Uta: Later.

Gaby: Better go before five thirty.

Uta: Yes, I’ll do that.

Gaby: How much money have you got?

Uta: I don’t know.

(A bit later.)

Gaby: Mama, can you move my left foot? (I do it.)

Can I go on the Pfanne when Papa gets back?

Uta: Yes, sure.

(She means when Peter gets back, she wants him to lie her on her bed, so that I can put her on her bed-pan.)

Gaby: Can I have a Vitamin C tablet?

I give her one. There’s some more noise from the mini-bike. Peter

returns.

Peter: I just remembered, I forgot to post your letter.

Gaby: God, how could you forget! — Can you post the letter, Mama? You have to go now because the letter-box gets emptied soon.

Peter: Mensch, ist mir warm! My goodness, I feel so hot and sweatty!

Uta: Willst Du nicht zum Pool gehen? Martin ist mit Wayne zum Pool

gegangen. Wouldn’t you like to go to the swimming pool? Martin did go

to the pool with Waine.

Peter: Ich bin schon ewig nicht am Pool gewesen. It’s been ages since I went

to the pool.

Uta: Ein bisschen Schwimmen würde Dir gut tun. A bit of swimming would be

good for you!

Apparently Gaby wants her letter posted before she goes to the toilet.

I get ready to post the letter and do some shopping. The mini-bike makes

an awful lot of noise again.

——–

Christmas Party Photos (1954?)

From Berlin to the Baltic Sea

Berlin is surrounded by the land of Brandenburg. In 2010 we travelled from Berlin through Brandenburg in a northerly direction. Where Brandenburg ends Mecklenburg-Vorpommern starts. The ‘border’ was marked by some signs near the road. We took some pictures of these signs.

Rheinsberg-Kleinzerlang is in Brandenburg. We took a picture of its marina.

With todays pictures is also included a postcard from the Baltic Sea resort Warnemunde as well as a picture from Warnemunde which we took ourselves.

I mentioned in another blog that we stayed in 2010 at my brother’s place in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. The picture of the lake is my favourite. This lake is just a few steps away from my brother’s property!

Excursion to Mt Keira

On the 14th of February in the year 2000 Peter and I went on an excursion to Mount Keira with our daughter Monika as well as Monika’s youngest daughter, who was two years at the time. Also with us was our daughter Gaby in her wheelchair. There’s a cafe on top of Mount Keira. The pictures were taken in front of that cafe.

From the top of Mount Keira there’s a beautiful view towards Wollongong and the surrounding area.

Gaby in pictures 1965 – 1971

Two of the photos were taken in November 1965 in Sydney’s Prince Henry Hospital, when Gaby was eight years old. She types with a mouthstick on an electric typewriter. During the day she is strapped in a high chair, her hands in braces.

The night she spends in an iron ‘cage’ with only her head outside it on a cushion.

Since 1961, when she was struck down by polio, she has been in Prince Henry Hospital’s Respiratory Ward. During the day she attends the hospital school class. Gaby is a quadriplegic, which means she cannot move her arms or legs.

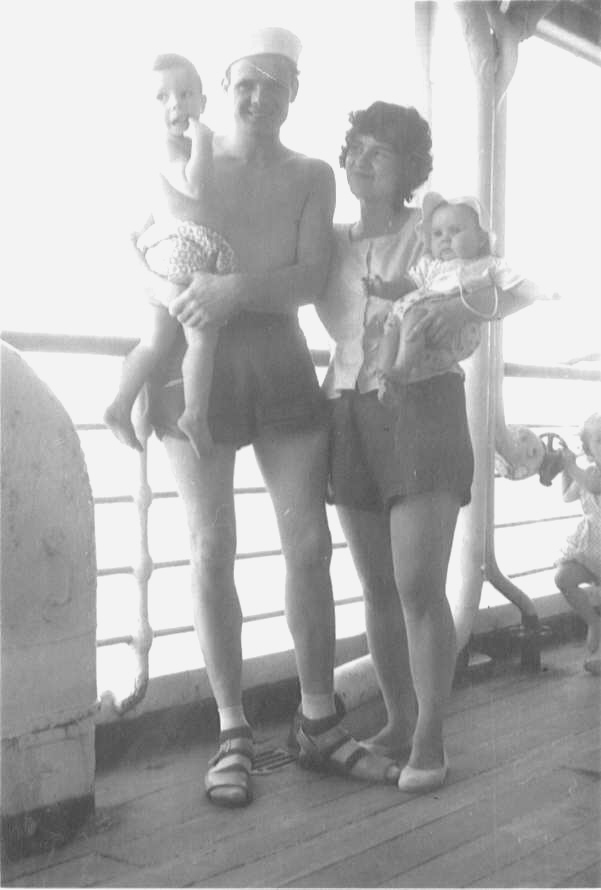

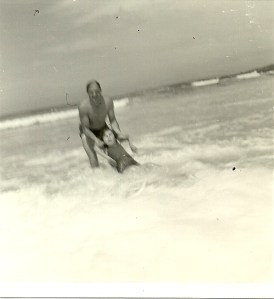

From January 1967 till September 1974 Gaby was able to live most of the time with her family, Mum, Dad, sister Monika and brother Martin. We took her on outings to the pool and to the beach. Peter, her dad, fastened her wheelchair to the back of our VW Beetle car.

In the pool I hold Gaby (13), Monika is 12 and Martin behind us is 11. I am 36.

In the photo Peter carrying Gaby out of the car and onto the beach, Gaby is probably 11 and Martin beside the car door is 9.

As far as I renenber we took Gaby right into the water at the beach only this once when she may have been only 10. Gaby was too scared of the waves. Even to the pool she didn’t want to be taken anymore later on.

Summer 1953

Fräulein Kubis was one of our lodgers. She was in her fifties, worked in an office and had never been married. Come Saturday afternoon, an elderly gentleman friend of hers would arrive for afternoon tea in her room. I think he never stayed for more than a couple of hours. Mum would call Fräulein Kubis ‘an old spinster’. She looked to me kind of bland, actually a bit like a mouse.

Fräulein Schröder was our other lodger. She was the most sophisticated lady I had ever come across. She was in her early twenties. She bleached her hair to a wonderful blond shade. The colour reminded me of cornfields. She came from a country town, had four younger brothers and sisters, who once came along for a brief visit. However none of her siblings seemed to be approaching her good looks.

I always called her ‘Fräulein Schröder’. She liked that, because she was of the opinion it would help to keep the relationship on a respectful footing. Fräulein Kubis called me Fräulein Uta, but Fräulein Schröder wanted to call me just Uta. However, she insisted, that she would address me with ‘Sie’ rather than with the more familiar ‘Du’. Fräulein Schröder was about seven years my senior. Through all the years that she lived in our apartment, she was always a very reliable friend to me. I could turn to her with any kind of problem. She listened to me patiently and gave me good advice, whenever I asked for it.

Before Fräulein Schröder moved in, she talked to Mum and explained, that she had a man-friend, who was often away on business. However, when he was in Berlin, he would like to stay with Fräulein Schröder over night. So she asked Mum, whether she would mind that. Since Mum had already met Herr W and judged him to be a ‘respectable gentleman’, Mum had no objections to the liaison.

Herr W often had to travel to Western Germany. In fact he frequently stopped in Düsseldorf to stay at his house there. When he heard, that my father also lived in Düsseldorf and that I wanted to visit him, he offered to take me along in his car. It so happened that after six months work at FLEUROP I was able to take my one week summer holiday. So with Mum’s blessings I went off with Mr.W to visit my father. Only, when we arrived in Düsseldorf, my father was not home. His land-lady had not been told, that I would arrive. She had no idea, whether my father had made arrangements for my staying with him. She was very doubtful whether it was proper, to let me in, especially since Mr.W offered, to put me up in one of the spare-rooms in his house. He said, his house-keeper would look after me. So I accepted the kind offer of Mr. W.

Mr.W’s elderly house-keeper had expected him and had prepared some delicious Klops (Meatballs) with Capers for the evening meal. Of course, she had not expected me to appear. However, there were enough Klops for me too. And a nice bed to sleep in! Mr.W knew that I did not want him to come close to me. Obediently he stayed away. I must say, his behaviour was that of a perfect gentleman.

My father had rented a very large, sunny room in a one story family home, which belonged to two ladies. One was elderly, the other, her daughter, looked to be in her thirties. Once the younger lady happened to enter the café where my father and I were having refreshments. My father invited her over and she sat down at our table and ordered coffee. Later on, when my father asked for the bill, the lady gave him the money for her coffee. Naturally my father objected and pointed out that she had been invited. She did not want to hear of it. She insisted to pay for the coffee herself. She said:

‘I’m an independent woman. I don’t want any man to pay for what I consume. Thank you very much, but I really feel better if you let me pay for my coffee.’ I thought by myself how very different from my mother this woman was. —

As it turned out, the old landlady was very caring and so was her daughter. When they found out, that my father had no bed for me but wanted to let me sleep on a mattress on the floor, they both objected. They straight away offered to let me sleep on a sofa in one of the living-rooms. They made up a very comfortable bed for me on that sofa. — The ladies always called my father very respectfully ‘Herr Doctor’.

The government had established my father on one of the floors of a modern, highrise office building. Dad introduced me to his secretary, Frau Kusche. I had the feeling, she was really pleased to meet the daughter of her boss. For lunch Dad met me in the office-canteen where excellent subsidised meals could be had. Instead of a beer to go with the meal my father ordered apple-juice for me. For me to have a drink like that was pure luxury. In those days I had not yet acquired a taste for beer. I said: ‘Daddy, I love this apple-juice very much!’ Saying this, Dad’s face lit up in a big smile. He wanted me to have a good time. He was pleased that a glass of apple-juice could make me happy.

When Herr W drove back to Berlin with me, he made a comment about my father’s lodgings. He said something like: ‘Your father knows how to pick a good place for himself!’ And when later on Dad moved into his own modern brand new flat, he said, ‘The government sure knows how to look after their Public Servants!’ I am sure, he did not mean it to sound nasty.

I knew that Fräulein Schröder was sometimes invited to spend time with some of Herr W’s family, who had a large family home in Berlin. Apparently no-one in the family had any nasty thoughts about Fräulein Schröder. How could they? She was such a kind and considerate person. On top of that she looked always classy in simple but very tasteful outfits which showed off her slender figure. I asked her: ‘Is Herr W not thinking of marrying you?’ And she said: ‘No, he can’t because he is married. His wife has been in a convalescing home for many years. He visits her as often as possible.’ And Mr. W? He pitied Fräulein Schröder that she had ended up being stuck with him. He said: ‘She should have a large family by now. Maybe to marry a park ranger would have been good for her.’

That night when I ended up sleeping in Mr. W’s house, he behaved – as I said – in a perfectly gentleman like manner. I am sure, Fräulein Schröder would have mentioned to him, that a year ago, at the age of seventeen, I had had an unhappy love affair, but that recently I had fallen in love with another young man. He probably also knew that I was totally inexperienced as far as a relationship with an older men was concerned.

In the car on the way to Düsseldorf he threw around some phrases such as that men were like bees who could fly from flower to flower. In a philosophical way this made kind of sense to me. However I myself certainly would not see myself as one of these flowers! So I already had made up my mind: No hanky panky with me, old buster! In due time he made a pass at me anyway or what I understood could have been a pass. We had had dinner in the kitchen while the house-keeper was serving us and talking to Mr. W about affairs that had to do with the housekeeping.

Experience must have taught W that a lady could alsways change her mind, if e.g. she felt very attracted and found it hard to resist the man’s advances.. Gallant Mr. W certainly would have regarded himself as being attractive to ladies. On the other hand, that he should find me attractive, flattered me in some way. However I had no intention of having an affair with him. As I said, I had already made up my mind.

After dinner he asked me into the living-room. I stood beside him as he put a record on. As soon as the music played, he lifted his arms to embrace me. Instinctively, I shrank away from him. I excused myself claiming to be very tired. I wished him a good night. I went to bed and it did not take me long to go to sleep. End of story.

A Job at last

A Job at last

Mum had been caught buying bread for us in the Eastern Sector of Berlin. For this offence the GDR Authorities put her into jail. When she came back home after having been incarcerated for about a week, she was full of beans. She regarded it as a big joke, that she had been jailed for buying a loaf of bread for her children!

The GDR law was that West-Berliners were not allowed to buy anything with East-Marks. In East-Berlin there were special shops for West-Berliners, were they could buy everything with West-Marks. One West-Mark was worth four East-Marks.. This was the official exchange rate! It was therefore very tempting for Mum to change her West-Marks into East-Marks and go shopping in the Eastern Sector as though she was a DDR citizen. Bad luck, that she was caught doing so. She did not feel guilty for trying to buy some low priced food for her children. Wouldn’t any mother do that?

Be that as it may, my brothers and I had to cope for one week without Mum. Tante Ilse, Mum’s sister, who lived across the road, saw to it that we were doing all right. Her husband, Uncle Peter, thought it was hilarious, that our Mum was in jail. He said: “What if somebody asks me ‘and how is your sister-in-law?’ shall I answer, ‘oh, she just happens to be in jail for a little while’ ?” For Uncle Peter it was somehow unimaginable, that anyone in his family should end up in jail. It was something just never heard of.

It so happens, that during Mum’s absence I did get my job at the FLEUROP Clearing House in Lichterfelde. The Boss, Herr Liebach, was not concerned that I wanted to leave Commercial College before doing final exams.

He said: “To me it is not important, whether you did the exams or whether you’ve done any University study. There are some University students who would be absolutely useless in our line of business. I judge myself, whether a person can be trained to do the sort of work that is required here. For instance, if someone is moving very slowly and takes ages to get a certain file from the shelf, for a person like that I have no use whatsoever. If you start here, you start from the bottom. You have to go through all the different departments, so that you are well aware of what everyone does. Then my secretary is going to start giving you dictations. If you’re good in stenography and typing and are able to produce business-letters ready for posting, you may end up here as a stenographer/typist.

He went on: ‘The first three months are a trial period. You start with a monthly salary of sixty Deutschmark. If you do well, your salary goes up a little each month. After the trial period you may get the chance to be fully employed with a fourteen months salary per year. The two months extra salary are for Christmas and for your two weeks holidays.Later on you may get three weeks holidays per year. We have a forty-eight hour week, working from 7,30 am to 4,45 pm. Saturdays we finish at one o’clock

When Tante Ilse heard about the low starting salary, she was up in arms. ‘What is that?’ she said. ‘This guy wants to pay you so little? You know what is on his mind? He wants to get you into bed! This is what he is after, I tell you.’

Good Tante Ilse. I don’t know what got into her. I was sure, Herr Liebach wasn’t like this. And the low salary, I didn’t mind that at all, as long as I could start there and did get some training along the way.

However when Mum was back home and heard I was only going to get sixty Mark monthly, she said immediately that I could not work for so little, because I would have to give her thirty Mark monthly. This was how much she got as student support for me as long as I went to school. She depended on this money. I said I was definitely going to give her these thirty Marks. ‘And what about train-fare?’ Mum said. ‘You need money for the S-Bahn when you have to go to Licherfelde!’ – ‘Never mind, Mum,’ I said, ‘I can pay for that out of my salary too. Most likely my salary’s going to go up soon anyway. So don’t worry. I really want to have this job.’

The Gypsies’ Prediction

I always thought that maybe the gypsies had

something to do with my coming to Australia.

One day Karl-Friedrich Liebach – our boss – announced: ‘Some gypsies approached me today. They offered to read the hands of all the employees. I paid them, what they asked for. That means, everyone of you can have their hands read, if you wish. And please do not pay them anything extra, because I’ve paid them enough already.’

I nearly missed the gypsies. It was lucky, that I caught them near the stairs, when they were about to leave. When I asked, could they foretell my future, one of them politely took my hand. She looked briefly at it Then she said:

‘You’re a lover of beauty. However you’re not going to stay here. In fact I can see you going to a far away country.’ With these words she and her partner hurriedly left the building.

During the years after the war, people with relatives in America were always dreaming of going to America for a better life over there. Indeed, people with relatives in America were very much envied, because it was assumed, that if you had relatives over there, you had a good chance of being accepted as a migrant.

None of my relatives lived overseas. However migrating to an overseas country was very much on my mind. Yet I assumed, that I had hardly any chance to be accepted as a migrant. In those days, I certainly never thought, that I might be able to go to Australia. However, this fortune teller had seen, that I had a desire to leave Germany.

It turned out, that some five years later I actually migrated to Australia! Did the gypsies really have anything to do with that? I wonder.