http://www.illawarramercury.com.au/story/2600053/the-ballad-of-living-treasure-lola-wright/

The Illawarra Mercury published the above story about Lola Wright, written

By ANGELA THOMPSON

The following is part of the article which I copied:

“Nothing went to waste in the Queensland bush tent where Lola lived for two years of her transient childhood.

Lola, still smoking away, living in a tiny community in central-western NSW.

Each day, her mother would sprinkle the dirt floor with water then sweep it, until the surface underfoot felt as solid as concrete.

The drawers and the kitchen sink were made of split kerosene tins and the legs of the cupboards were cotton reels, stood inside old condensed milk cans filled with kerosene, to deter ants.

Lola slept in a bush bunk made from a chaff bag suspended between two forked tree branches.

The hammock-style arrangement was a marvel of 1930s bush ingenuity, though its frailties were exposed on stormy nights when the family’s frightened collie dog would take refuge underneath, only to later stand up and butt against the bag’s underside, expelling the sleeping child.

The tent had only two real pieces of furniture – a double bed for Lola’s mother and father and a wind-up, Gramophone-style record player. Whatever would come, with Lola there would always be music.

Lola was taught to play the piano by nuns at her school but taught herself the accordion she played in the bush band.

‘‘When [the record player] ran out of needles, you’d use a straw out of the broom,’’ Lola remembers.

From her current home in tiny Morundah, a town near Narrandera consisting of little more than a hotel, some silos and houses for 22 residents, Lola looks back on the bush tent as the last real home of her childhood. She, her mother and little brother Billy had long followed her father from job to job, arriving at the camp in Dotswood Station, where the family’s ‘‘gypsy’’ patriarch cut timber for the railway, in 1934. But her parents soon divorced, and life became more uncertain. Lola was sent to boarding school and never knew where she would spend her holidays, or with which relative. Looking back, she attributes her decision to marry young – at 21, to a man she would later divorce (‘‘a good choice who just went bad as he got older’’) – to a want for stability. ‘‘I lived in a suitcase until I was married,’’ she said. ‘‘Then I had my own flat, my own things in my place – and it was very important to me.’’

Billy had been unwell for much of his childhood and was in care when Lola went to boarding school. Unbeknown to the family then, the eight-year-old had Hunter Syndrome, a rare and serious genetic disorder that mostly affects boys. The condition is caused by a lack of the enzyme iduronate sulfatase. Without this enzyme, compounds build up in various body tissues, causing damage. Lola’s father came to collect her one day, telling her: ‘‘we’ve got to go and bury Billy, he died’’. ‘‘I was a little bit sad but he had nothing to live for, poor little fellow,’’ Lola said.

Tragedy arrived again in 1942 when Lola’s father, Harvey Cowling, became a prisoner of war during the Japanese invasion of Ambon, in Indonesia. Cowling went to Ambon as part of the field ambulance and was captured almost immediately. He remained a prisoner for three years before he emerged weighing about 40kgs, with a pot belly from beriberi. Lola was there to greet him when he stepped off a ship onto Australian soil again, in 1946.

‘‘I couldn’t feel the sad things about him, I just knew it was my father,’’ she said. ‘‘It was just overwhelming to even think about meeting him when he got off the ship. All the love I had for him just flowed out, I couldn’t think about anything else. We were really good mates.’’

Nuns had taught Lola to play piano at boarding school and she later taught herself to play the accordion. She could often play a song after a single listen and had an uncanny ability to remember songs, from the very old songs her grandmother passed down, to the traditional Australian folk songs she picked up around the campfires of her family’s transient days in the 1920s and 1930s. During the 1950s and 1960s, when she campaigned for women’s rights and aligned herself with Communism, she favoured anthems about solidarity and women’s rights.

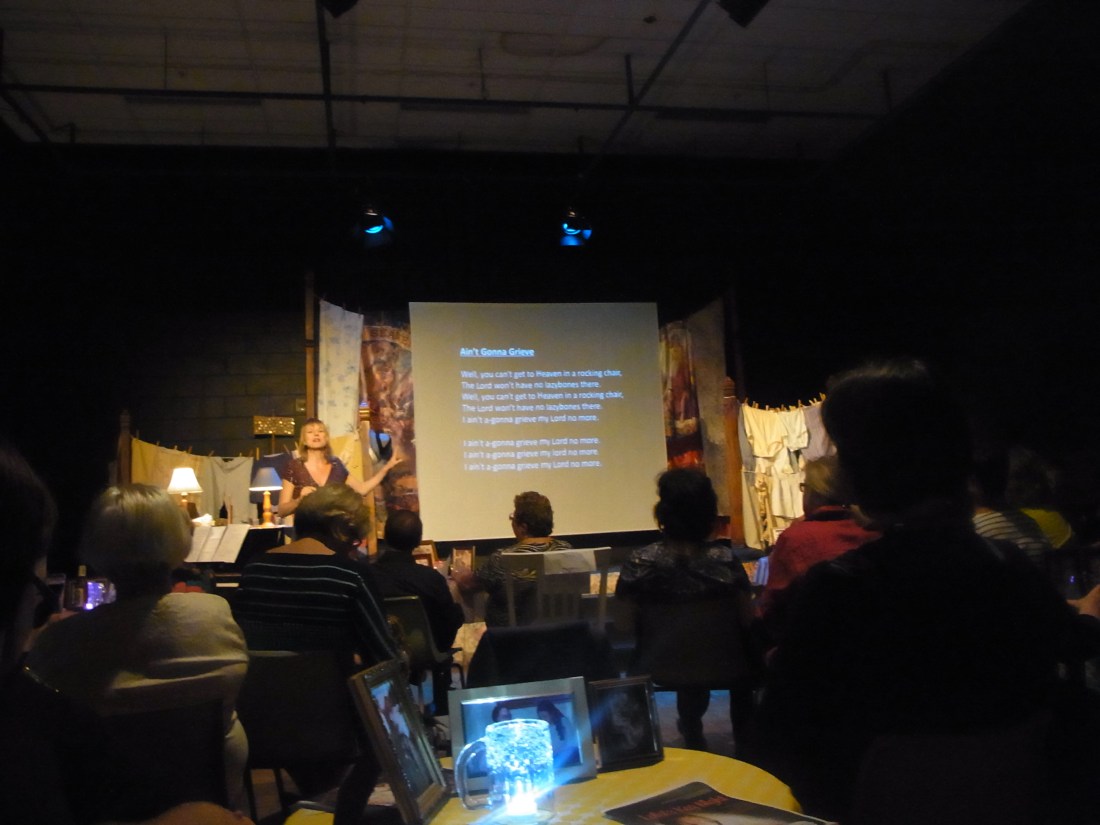

Her incredible internal archive – estimated to include 600 songs – brought her to the attention of the National Library, whose recordings were discovered by Randwick producer and musical director Christina Mimmocchi. Mimmocchi was struck by the story ‘‘of a very resilient woman’’ and the ‘‘great character’’ that started to emerge alongside the music-focused recordings. The resulting play, Lola’s Keg Night, is a musical memoir adapted by Mimmocchi and Sutherland playwright Pat Cranney, who recognised in Lola a role model and early feminist. In the 1950s nad 1960s she had helped popularise a song called The Equal Pay Song, written to support the campaign for female teachers to be paid the same as their male colleagues. ‘‘She didn’t take being treated badly by husbands,’’ Cranny said. ‘‘She left them if the relationship wasn’t working – she was quite a strong women.’’

Mimmocchi and Cranney drew directly from the library recordings, and Lola’s unpublished autobiography, to develop a verbatim play that will premiere at the Illawarra Performing Arts Centre on October 9. They named it after the keg nights Lola and her long-term escort, Bill, would host in their Horsley Road, Oak Flats home in the late 1970s. Lola’s teaching friends, Bill’s fellow wharfies and various Labor Party mates had a tradition of meeting in an area pub on Fridays. But the gatherings were moved to Lola’s when the group’s relationship with the publican broke down. Bill would procure the kegs and Lola would take her piano accordion out on the front porch and oversee rousing sing-alongs. She was encouraging, with a schoolteacher’s authority and a knack for getting everyone involved. ‘‘People follow her instructions, so if she said ‘you’re not to touch that keg until you’ve sung Solidarity Forever’, they’d listen,’’ Mimmocchi said. To the bad singers she gave a set of spoons to play, or a lagerphone.

They were instruments she was well familiar with by then. In 1958, inspired by an appearance by Australia’s first bush band in the musical Reedy River, she formed the South Coast Bush Band with a group of friends and her second husband, Coledale Labor Union icon Jack Wright.

The South Coast Bush Band was in demand for union demos, fund-raisers and dances.

Lola was the only one with any musical knowledge, but the band was in demand at local dances and miners’ strikes, school fundraisers and trade union functions. In 1959 they played in Petersham Town Hall to celebrate Dame Mary Gilmore’s 90th birthday. In her autobiography, Lola describes how the others compensated for their lack of musical training. ‘‘The blokes were all extroverts with good voices, good presentation and a sense of rhythm,’’ she wrote. ‘‘Normal Mitchell, Winifred’s better half, played the lagerphone – better than any I had heard before or since. Jack Wright played bones that he rattled like a professional. Merv Haberly played mouth organ and Johnny Chalmers played bass – bush bass, that is. That needed no expertise, but his voice was as magnificent as his huge frame.Our band was formed, not to make money, but to spread Australian folk songs. At the time we were being inundated with Yankie Folk Songs and ours, which are equally as good, were being ignored.’’

Lola was a champion for Australian culture and carried this into the classroom over a 40-year teaching career that took her to about 10 Illawarra primary schools. In a submission to a book published in March 2012 to mark the Centenary of Coledale Public school, former student Michelle Harvey recalled her ‘‘incredible teacher’’ from the 1950s. ‘‘She introduced us to a love of learning. We learnt much of our own country and some of its culture. She became an inspiration to me for the way she radiated warmth and responsiveness to us kids.’’ She liked to get kids singing and playing percussion instruments, and led giant sing-alongs in the schoolyard. She was always looking out for the underdog and ‘‘the child who needed extra love’’, said colleague and friend Lenore Armour.

Lola Troy (later Wright) and her first daughter Denise.

‘‘But she didn’t muck around. She wasn’t soft, she was absolutly respected’’.

‘‘She was a risk taker, she would bend the rules a bit. She cared about the learner, not the subject, and she had results.’’

Lola had two daughters (her son, Peter, died in infancy), and had two marriages behind he when she started seeing Bill Everill.

Their attraction sparked at a progressive bush dance in Wollongong.

‘‘How are you?’’ asked Lola.

‘‘Any better and I’d be dangerous,’’ Bill replied.

‘‘That’s how I like my men.’’

The dance separated them, but Bill arranged a later introduction. It was love.

‘‘The first thing that struck me was the way his blue eyes could twinkle,’’ Lola said.

‘‘He was a man who was well read, loved music, was gentle and understanding.’’

Bill was married to a Catholic woman who wouldn’t give him a divorce, so he and Lola weren’t married until 1986, 13 years into their courtship. They moved together to an acre of land in little Morundah and had 14 good years together before Bill’s heath started to fail.

Lola nursed him through a suite of illnesses for the last six years of his life, including dementia towards then end.

Bill stayed at home until seven days before he died. At the hospital, a nurse told Lola she had performed the work of five nurses in caring for him.

Lola sat quietly at Bill’s bedside and stroked his hand until he died.

‘‘There was no drama about it except I had a friend with me who was a clairvoyant,’’ Lola said.

‘‘We were in a hospital room and of course it was air conditioned, but she went and opened the window. I asked her why, and she said, ‘to let the spirits in to take Bill’s soul away’.

‘‘A week later she walked in and saw a photo on the table and said: ‘who are they?’. I said, they’re Bill’s maternal grandparents. She said ‘oh my goodness, they’re the ones that came to take him away’.’’

Lola looks back on her bush upbringing and thinks it taught her to be friendly. There weren’t many people around, so was important to get along. ‘‘Often you need things and you can share things – your life and our time and your abilities. I think that it’s the sharing and caring that I got from living in the bush.’’ In Morundah, Lola was still mowing her own lawn until six months ago, when she started making socks for the younger residents, so they will do it for her. She buys her bread from the pub, which doubles as a corner store. On Friday nights you may find her there.

‘‘There’s a good crowd,’’ she said.

‘‘There’s only 22 of us but we’re all good mates.’’