Before and After the War

Extracts from my Memories

In 1942/1943 my friends in Berlin and I had often contemplated what life might be like, once we had peace again. Our dreams for the future were very basic. We all wanted to get married and have children. We all wanted our husbands to have occupations that would enable us to live in comfortable houses. My friend Siglinde and I were for ever drawing house-plans. There would be at least three bed-rooms: one for the parents, one for two boys and another one for two girls. Yes, to have two boys as well as two girls, that was our ideal.

Before we married, we would finish school and go to university and our husbands would of course be university educated. In peace-time we would be able to buy all the things we had been able to buy before the war started: Bananas, pineapples, oranges and lemons; all this would be available again! Somehow we knew, we were only dreaming about all this. We had no idea, what would really happen, once the war ended.

I turned eight in September of 1942. Most of my friends were around the same age. My friend Siglinde however was four years my senior, the same as my cousin Sigrid.

After I started high-school, some time after the war had finished, Cousin Sigrid made a remark, that put a damper on my wishful thinking. Sigrid had noticed, that I got very good marks in high-school. So she said in a quite friendly way: ‘I see, you’ll probably end up becoming a Fräulein Doctor!’ This remark made me furious inside. It sounded to me, that once I embarked on becoming a ‘Fräulein Doctor’ I would have no hope in the world of acquiring a husband and children. ‘Who in their right mind would study to achieve a doctorate and miss out on having a husband and children?’ I thought to myself.

Mum, Tante Ilse and Uncle Peter loved to read romance and crime fiction. Most of the books they read were translations from English. Mum and Tante Ilse loved Courts-Mahler, Uncle Peter liked Scotland Yard stories best. They all had read ‘Gone with the Wind’. Even my father, who boasted, he never read any novels, read this one.

I read ‘Gone with the Wind’, when I was fourteen. My father’s sister Elisabeth, on hearing this, was shocked, that my mother let me read this novel. According to Tante Lisa, I was much too young to read something like this. However some of my girl-friends read this book too. They all loved Rhett Butler. About Scarlett the opinions were divided. Personally I did not care for the way she treated Melanie. I thought by constantly making passionate advances towards Ashley, she showed total disregard for Melanie’s feelings. Rhett adored Melanie. He showed her great respect as a person with a noble character. In contrast, he was well aware that Scarlet was anything but noble. Often he found Scarlett’s irrational behaviour highly amusing. Ashley treated Scarlett in a very gentleman like way. Not so Rhett. This impressed my friends. They all admired Rhett! I think, I admired Ashley more. –

Mum and Tante Ilse borrowed books from a lending library. A middle-sized novel cost one Deutsche Mark to borrow for one week, a real big novel cost two Marks. In secret I once read a translation of ‘Amber’. Fascinating stuff this was.

When I read ‘Amber’, I was probably thirteen. I read it only, when I was by myself in the apartment, which happened often enough. I was able to consume the whole big novel without anybody noticing it. I knew, Mum and Tante Ilse had read the book already, because they often talked about it, how good it was. But the book was still lying around at our place. There were a few more days before it had to be returned to the library. I found out, that Amber was a fifteen year old country-girl, who went to London. The time was the seventeen hundreds. Because of her beauty, Amber was able to make it in the world. She had lots of lovers. She always made sure, that her next lover was of a higher ranking than the previous one. That made it possible for her, to climb up the social ladder. – Well, this is about as much as I still remember from that novel.

During the first years after the war we lived like paupers. Still, I realized – maybe a bit to my regret – that there was a big difference between a desperately poor girl from the country and me, desperately poor city girl from a ‘good’ family. I knew then, whether I wanted it or not, I had to put up with an extremely low standard of living for some time yet. And I mean by ‘low standard’ not the low standard that everyone went through during the adjustments after the war, but a standard, where it was necessary for us to get social services payments!

Was I out to enhance my appearance in order to catch a prosperous male as an escort to take me out to fun-parties and adult entertainment? No way! Something like that was just not for me. I felt I was plain Uta who was never invited to go out anywhere with anyone.

Was I really that plain? I wonder. Up to age fourteen I may have had some chances with the opposite sex, given the opportunity. However by age fifteen I had put on so much weight, that I felt to be totally unattractive. I was right, because no attractive male ever made an attempt to woo for my attention, not until I was about seventeen and a half that is. But even then things didn’t change much for me. I honestly felt like some kind of a social freak during most of my teenage years.

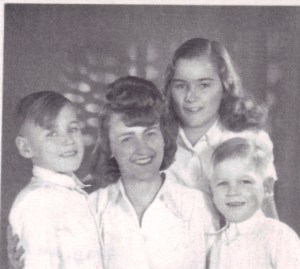

Here is a photo which was taken in 1948 with Mum

and my brothers, who were 7 and 10 years and I was 14.